The first (and second) Model Ts rolled off the Ford Motor Company assembly lines in 1908, scarcely 20 years removed from the first class enrolling at the Georgia School of Technology. As dirt gave way to asphalt, and car culture captured the country’s imagination, young engineers and mechanics in Atlanta’s North Avenue shops and foundries were instantly drawn to automobiles and the pursuit of speed. Racing culture blossomed in and around Atlanta, and Georgia Tech was at the epicenter. This culture would influence the origins of stock car racing and the beginnings of NASCAR, the most popular motorsports series in the U.S.

The Indianapolis of the South

Georgia Tech students published the first issue of The Technique in 1911, the same year that custom-engineered, open-wheel cars raced the inaugural Indianapolis 500. Less than a decade later, Tech students were among the throngs flocking to the new Lakewood Speedway, seven miles south of campus, to watch some of the earliest organized auto racing in Georgia. Dubbed the “Indianapolis of the South,” the mile-long race track hosted many of the region’s most prominent competitions, including annual, multi-race exhibitions on Independence Day weekend.

With the dawning of Prohibition in 1920, several of the featured racers became locally infamous for their off-track driving skills as “trippers” — transporters of illegal corn liquor from the hills of northeast Georgia to the Atlanta area. Their law-flouting experiences driving souped-up stock Fords on the dirt roads of rural Georgia translated into raw speed on the tracks at Lakewood. These rough-and-tumble events were a wash of red dirt clouds, deafening engines, and gasoline fumes — the perfect concoction to attract the best drivers, mechanics, car owners, and auto enthusiasts from across the Southeast. It would not be long before Georgia Tech students got behind the steering wheels of their own racing machines.

The Old Ford Races: Clean Old-fashioned Hate Takes to the Road

“EVERY MAN FOR HIMSELF,” proclaimed the May 3, 1929, front page of The Technique, announcing its sponsorship of the first Old Ford Race (also documented as the Flying Flivver Race). Inspired by Dean of Men Floyd Field’s 1914 Model T and news coverage of a 1927 cross-country event at Oklahoma State University, Georgia Tech students challenged their University of Georgia rivals to race jalopies along the rough, 79-mile country road from Atlanta to Athens on Saturday, May 18.

“Come on boys, don't be bashful. It doesn't cost anything to enter this road race,” the writers urged. Only four vehicles managed to cross the finish line. The rest ended up in heaps along the roadside that is now U.S. highway 78. The fastest time recorded was 1 hour, 26 minutes, at an average speed of 55 mph (the typical pit road speed limit for modern stock car races). The following spring, 16 student-piloted cars, including an entry by the Yellow Jackets football team, competed in the second Old Ford Race. With increased local attention and a tighter set of rules (set by Technique staff), all but one vehicle finished.

In 1930, days after the second Old Ford Race, the Atlanta Constitution reported on the Intercollegiate Motor Marathon, a school-sanctioned, invitation-only event for college racers. Student drivers from Georgia Tech, UGA, Mercer, University of Tennessee-Chattanooga, Oglethorpe, and Auburn were slated to race from Athens to Lakewood Speedway. While teams from Mercer and UGA were able to make their speed runs the afternoon of May 17, heavy rains kept most student racers off the roads and indoors for the remainder of the weekend. For reasons not clearly documented, the rescheduled race to determine the fastest college driver in the Southeast never took place.

These increasingly fast and furious competitions proved too dangerous for Dean Field and other administrators, who put a stop to the Old Ford Races after the second and final running in 1930. To mollify students over the cancellation and maintain the spirit of building creative contraptions, two years later the dean and the Yellow Jacket Club transformed the races into the Ramblin’ Wreck Parade, a tradition still held each year on the Saturday morning of Homecoming weekend. Dean Field led the inaugural parade behind the wheel of his 1914 Ford Model T — the first unofficial Ramblin’ Wreck mascot.

During this time, a teenage entrepreneur named Raymond Parks moved from his family home in Dawsonville, Georgia, to Atlanta to help operate his uncle’s service station at 717 Hemphill Avenue. As a purveyor of illicit liquor, meeting the high demand for moonshine had made him a millionaire. “That was my living and I don't mind telling people I was in it,” Parks mused in 2000. “Back then, that’s the only way people up in the mountains had to make a living.” Among the men running whiskey for Parks were his cousins Lloyd Seay and Roy Hall, two of the most daring drivers in Georgia. He ultimately bought the Northside Auto Service and Hemphill Service Station, opened a number of other legitimate businesses, and continued his lucrative bootleg whiskey operation. Soon, however, Parks’s cousins hooked him on a new venture: stock race cars.

Often to the dismay of administrators, the reference to distilled spirits in Georgia Tech’s world-famous fight song has been a part of campus lore longer than the Ford Model T. And for many of the “jolly good fellows” at Tech, their prime local source for clear whiskey was Raymond Parks. His service station and package store were magnets for budding engineers at Georgia Tech. He treated them like family, cashing checks and extending store credit for his peers in a pinch. Students drove test runs down Hemphill and North Avenue to 565 Spring Street, the nearby home base of another eventual racing legend, master mechanic Red Vogt.

Vogt secured his reputation building and customizing cars for moonshine delivery. In his namesake garage just southeast of campus, Tech students often watched and learned as Vogt built some of the fastest early stock cars. His son, Tom “Little Red” Vogt, recalled working in the famed speed shop. “It was filled with Georgia Tech engineering students,” he said. “In and out, day and night. They wanted to hang out because of the colorful place, the bootleggers, and my dad’s reputation for building fast cars. They all wanted him to build the engines for their cars and always wanted to talk to him.” The respect for Tech students was mutual, as Vogt placed paid advertisements in the Blueprint yearbook each year from 1940-1946.

In 1938, as Georgia Tech celebrated its 50th anniversary, driver Lloyd Seay won the first official stock car race at Lakewood Speedway in a Parks-owned car built by Red Vogt. Together, Parks, Vogt, Seay, and Hall soon became the first dominant team in the sport. One of Seay’s competitors in that 1938 race was Bill France Sr., a Florida-based entrepreneur, promoter, and racer who first met Parks in Vogt’s Atlanta garage. Nine years later, France would invite the two of them to help create a national sanctioning organization — the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing, or NASCAR.

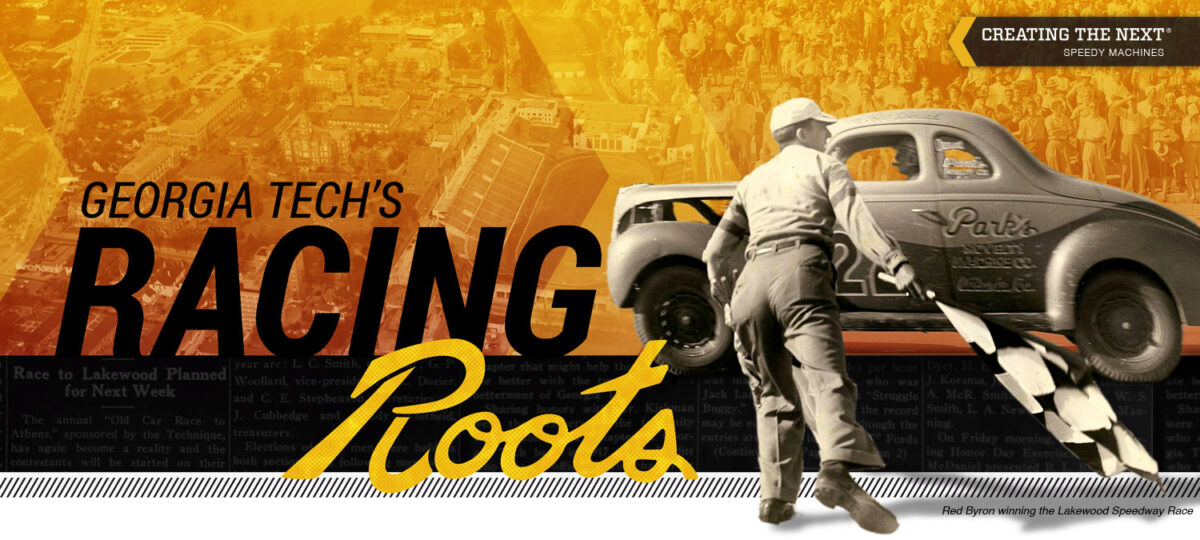

In December 1947, France organized a series of meetings with 35 key players in the stock car racing business — including Parks and Vogt — at the Streamline Hotel in Daytona Beach. Parks provided much of the initial funding, Vogt devised the rules and suggested a catchy, acronym-based name that he and his wife Ruth had come up with years earlier as part of his Georgia racing charter: NASCAR. The meetings resulted in the formation of the nation’s premier stock car racing series. During the first official season in 1948, Parks’s driver and fellow World War II veteran Red Byron cemented the team’s legacy, winning the first race on the sands of Daytona and capturing the first series championship. After winning that inaugural title, Byron opened his own namesake speed shop at 719 Hemphill Avenue, adjacent to Parks's Hemphill Service Station.

Parks began to back away from the sport in 1950, at the peak of his team’s success. By that point, his driver Red Byron had found Victory Lane at every major track in the South, and his Red Vogt-built cars had won multiple times at each. Among his last recorded events as a car owner were entries for Byron at the new Peach Bowl short track off Brady Avenue and Marietta Street, just west of the Georgia Tech campus.

Georgia Tech and the Parks Legacy

Raymond Parks focused his post-racing years on running his Parks Novelty Machine company and other Atlanta businesses, several of which remain in family operation to this day. In the early 1960s, he sold some of his properties to Georgia Tech, providing prime real estate for the Institute’s northward expansion. The former site of the Hemphill Service Station and Red Byron Auto Service is now the heart of the Georgia Tech campus, near the Kessler campanile and the Student Center.

The Georgia Racing Hall of Fame in Dawsonville formally recognized Parks for his contributions to the sport, inducting him into its first class in 2002, along with his trusted mechanic Red Vogt and drivers Byron, Hall, and Seay. Less than a year before his death in 2010, Parks was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in Talladega, Alabama. Most recently, NASCAR announced his name among its 2017 Hall of Fame inductees, an honor that finally secured his proper place in American stock car racing history. During development of this feature, the NASCAR Hall of Fame announced that Red Byron will be enshrined in January 2018. Vogt has yet to receive the distinction, despite his significant contributions. The bays of his former garage now serve as the entrance to a law firm that occupies the renovated building at Spring Street and Linden Way.

Today, Georgia Tech remains true to its racing roots, as home to six competitive motorsports programs that offer students opportunities to apply their engineering knowledge to the pursuit of speed. During a recent visit to campus, Raymond’s wife, Violet Parks, and her son Steve White toured the Student Competition Center on 14th Street, just down Northside Drive from the family’s still-active businesses. “The facility was amazing to me,” she remarked. “It seemed like they had everything in the world to work with.”

Her support is more than casual or nostalgic. In 2013, she made an estate gift that will one day establish the Raymond D. Parks Scholarship Endowment, providing scholarship support for mechanical engineering undergraduates who participate in the GT Motorsports Program. It is a tribute to the man and to generations of Tech students passionate about fast, efficient cars. “We wanted a permanent legacy for Raymond in Atlanta, which he loved so much, and Georgia Tech was the place to do it,” Parks noted. “He cared about helping people, and it’s fitting that we are doing something that will help undergraduates in the future. I think it would make him happy.”

The Racing Roots of Georgia Tech is the first in a three-part series on motorsports innovation and culture unique to the Institute. Join us in July to learn how a Georgia Tech professor helped break a world speed record at Daytona, meet an alumnus who revolutionized racing safety equipment, and explore a number of other motorsports stories surrounding Georgia Tech researchers and racers. Later this summer, current Yellow Jackets share how they're creating the next speedy machines and our experts envision the future of racing.

- Doug Goodwin, Georgia Institute of Technology